Entry to Pioneer Park featured a sign warning that Sally Rippin was unable to attend and the number of kids in the audience suggested this was sad news but they didn't leave without being informed and entertained.

Information came from local author Caroline Tuohey, who gave an introduction to professional writing. "Who plays sport?" she asked. "Who plays a musical instrument?" These pursuits she explained were similar to writing in requiring lots of practice.

Tuohey compared the sense of disappointment from missing a goal to that of receiving a rejection letter from a publisher. "What do you do?" she asked the crowd and a girl replied "You try again".

"You might go on like this all season," Tuohey continued, "but when you do score a goal you do a silly dance." She explained that she would've done a somersault when she opened the acceptance letter from her publisher, if she'd been able to.

"I was so excited that half of New South Wales would've known I was being published by the end of the day."

Her message to the kids was clear, if you want to succeed as a writer, you keep working at it. She encouraged them to keep a notebook, before asking who had a Nintendo DS. "Use it to write and keep track of your ideas," she advised.

Tuohey asked the crowd if anyone had a story they want to write and a boy named Hamish shared his idea. It involved a guy falling into a shark tank and being saved by his exploding underwear. When asked how many sharks were in this tank, he answered "Five thousand, ten hundred and ninety-six".

"Can you see how chatting about stories leads us to develop ideas? It's called brainstorming," said Tuohey, leading the crowd to brainstorm for stories about moving house.

"We've got a few good stories here," said Tuohey. "Let's take one. I know someone who accidentally packed their pet. It ended up in a box in the removalists' van and you'd think 'please don't vomit'. What if it makes a mess?

"This kind of 'what if?' question is a good question. Writers use it all the time. It's an important question because you come up with all sorts of ideas. What if you were packed in the removalists' van? Would you use your exploding underpants?"

"I already did!" exclaimed Hamish.

Tuohey advised the young writers to keep a notebook handy to develop their work. "It's very important to put ideas onto paper."

Leading into the conclusion she observed "I'm very pleased you're here today because it means you're readers". She explained that the slow bus ride to and from school in Hay had given her time to pursue this activity. "I read 798 books -- in year seven," she declared. "I hope you keep reading for the rest of your lives."

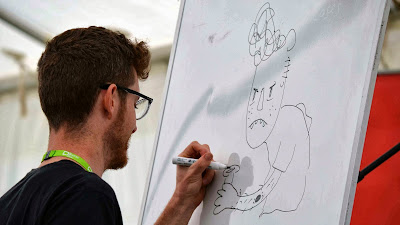

Graphic novelist Pat Grant took to the stage briefly to bring a whiteboard down to the front of the crowd. He introduced himself and explained he uses drawings to tell stories. Drawings in sequence to create comics.

"You might think I came here to talk to readers and writers but I came for ideas," he said.

"A shark with a man-eating head!" exclaimed Hamish, who went on to also suggest a camels body.

"What can we do to make him cooler?" asked Grant.

A girl suggested this camel-shark should eat hot dogs and Grant dutifully sketched these ideas.

"We need a protagonist and an antagonist," he explained. "Which is fancy talk for a good guy and a bad guy."

It was settled the camel-shark would be the good guy.

"Who's the bad guy?" asked Grant.

"You are!" came a reply and so Pat Grant began sketching himself, while explaining the characteristics that would display moral shortcomings such as bad posture, hairy arms and a tattoo.

"What else?" asked Grant and the reply was for one leg.

"That's great," he enthused. "What do we call that? That's motivation."

Through this process of crowd-based brainstorming a story developed involving a glass-bottomed container ship stacked with Ikea furniture, where Bad Pat would attempt to poison the camel-shark with a frankfurter. This bait was to be fed through a hole in the glass until physics intervened, capsizing the ship and putting Bad Pat within striking distance of the camel-shark.

"What else?" asked Grant. "A coda maybe?"

"Lightsabres sticking out of the water!" proposed Hamish and it was suggested this might be material for a sequel.

This session concluded with the children being directed outside for face-painting.

Allen and Unwin publishing representative Deb Stevens took to the stage with the first panel of authors. She acknowledged the Wiradjuri people "because this is a festival of storytelling and they had an oral form of history through storytelling".

Author Peter Rees spoke next outlining his path to writing history from journalism in the Riverina. He'd been introduced to the stories of the Lancaster Men for his recent book of that name and surprised to learn how they'd been marginalised by history despite their contribution and high mortality rate.

"Only the Nazi U-boats had a higher death rate," he said. "You had to be in awe of them for taking their lives in their hands."

Rees gave examples of the larrikin behaviour of some of these men, including clearing the best seats in the British-dominated RAF common room by throwing 303 bullets into the fireplace and flying a Lancaster under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. He described the latter as "an example of the daring they could get away with" while acknowledging it was hard to imagine such an event happening in the present day.

He characterised the letters sent by the Lancaster Men to their families as "the epitome of Australian experience" through their use of metaphors, One described a bombing run like going on a picnic, while another described the sight of shells exploding around the plane as being like the Dimboola Regatta. Another compared the searchlights combing the skies as they flew to standing naked on stage at a theatre.

Of course, the real resonance in the material came from the possibility of death for both the bombers and the bombed, "The thought of it makes me sick but we have to do it for the greater good," Rees recounted one letter writer as reflecting. Another wrote a letter to be delivered in case he died: "Know my heart is at ease… Cheerio, keep smiling though your hearts are breaking."

Through this research Rees "gradually built up a picture of these young men" who were derided on their return after the second world war as "Jap dodgers". One of these was Sir James Rowland, who very nearly didn't get to become the Governor of NSW after being captured by Gestapo and rescued from the firing squad by Luftwaffe airmen who believed in a "brotherhood of airmen".

This was one such story of humanity from the war and, despite having an old-fashioned air, it's emotive material. It seemed clear that, for a former journalist, it is this humanising of the story that is an important element in Rees' work.

Roland Perry was next, speaking to promote his 27th book Bill The Bastard. Perry was the stand-out speaker of the day as he actively sought to engage his audience, constantly scanning the crowd and responding to their body language in a way that made his delivery more like a conversation.

The titular Bastard was one of over 200,000 horses sent from Australia to assist in the first world war, which had included around 1,100,000 such animals. Bill was something of a mongrel with "the legs of a thoroughbred and the body of a draught horse". His cantankerous disposition was due to being handled roughly and branded early in life, leaving a deep mistrust of humans.

"Bill was used almost as a cynical joke to test the city-folk who wanted to join the lighthorsemen," explained Perry. Sent to war, the horse worked on the mail run at Gallipoli. It was such a dangerous task that Australian and British soldiers would cease fighting to place bets on the likelihood of success each day.

Major Michael Shanahan was impressed by Bill and decided to make him a warhorse and spent three months breaking him. Perry noted it wasn't widely known that poet Banjo Patterson oversaw 800 breakers during the war.

Bill's most distinguished service was in the General Sir Henry George Chauvel-led offensive against the Turks in the Sinai desert:

His greatest feat was to save the lives of his master and four other men who clambered on him to escape at the battle of Romani in the Sinai on 4 August 1916. After cantering, under fire, several miles to Australian lines (and using his hooves to cave in the chests of two Turks who tried to shoot him) he took a drink and pawed the ground, indicating he wanted to return to the action. The Turks were massacring prisoners and he undoubtedly saved the five men.Around this point Roland Perry stopped to comment. "What I am looking for in all my books is the narrative and the characters." Bill the Bastard brought together both and I often think the best dramas have a backdrop of intense social upheaval, like war.

When Shanahan was unconscious with one leg smashed by a bullet, Bill carried him gently and without directions several miles to an aid post.

Perry spoke about his forthcoming book about a dog that served in the second world war, making it clear that he wasn't aiming to be known for writing about animals serving in combat. He indicated toward Peter Rees and said, "we're looking always for the human content in war" and I guess the relationships of humans with animals adds further interest, as well as humanising history in an engaging way.

After some discussion of the authors works outside of war history, Perry made an observation about his motivation to write:

"You've got to have a passion for the subject matter. You're on your own and you have to feel very strongly about the subject" to get through the process of writing a book. "You must not be motivated by what is popular."

It was interesting that Perry shared how happy he was to have written a book that interested female readers. Cynically one could suggest this is because most buyers of books are women and, looking around the audience at the Readers Festival this seemed to be true. But I'd guess that war is not usually an interest for females, so there was a challenge in that anyway. It got me thinking about Michael Lewis' observation “You never know what book you wrote until you know what book people read”.

Next, local authors and writers were invited to present five-minute presentations about their current works, projects and publications.

Barry Walsh hung a poster showing the "sacred geometry" in the designs of Griffith and Canberra, then spoke on connections between disparate events. It was difficult to follow but fascinating to listen to in a 'WTF?' sorta way. His line "copyright misunderstands fiction" caught my ear.

Jo Wilson-Ridley discussed her poetic responses to exhibitions she'd seen in Griffith, which I thought was an excellent approach. One show had been a collection of polaroids taken by a photographer documenting war crimes in Iraq and she asked "what do we do when logging off from depravity?'

Caroline Tuohey returned to the stage to discuss the fiction and non-fiction she'd had published, as well as poetry on coffee mugs and tea towels that she sold at markets. She presented a bush poem about the drought called 'Riverina Rain' that was really good and resonated with an understanding of how this recent event had affected the lives of those who live on the land.

Martin Mortimer introduced his science fiction work under the pen-name M.R. Mortimer. "Each book I make is a little different as I need to challenge myself," he explained before reading from his "space opera" Armada's Disciple.

Susan Toscan spoke on her book La Strada Da Seguire: The Road to Follow, a fiction covering the period before and after the second world war and "the combining of Australian and Italian cultures, which we know so well in Griffith". The book is loosely based on the people she's known and stories collected have been embellished as a way of preserving them for future generations.

(Sorry Susan, I missed getting a pic of you.)

Natalie Hopwood was "excited to be here as a writer and lover of books". She read from her book on growing up in Barellan, "the town with the biggest tennis racket". It was quite poetic and I liked the line about how, if it wasn't for football and netball, no one would go out in winter.

Rozanne Gilbert spoke of writing over 100 poems and plans to write a fiction based on her life experiences. She writes a column for Wagga's Daily Advertiser and recently performed a play in the Leeton Eisteddfod.

Amanda Robins introduced herself as a marketer before a writer, who'd wanted to produce something that was "helpful as well as enjoyable" in her work How to Turn On a Tired Housewife. "It's something simple people can relate to," she said. A lighthearted picturebook that aims to educate men to offer caring rather than grand romantic gestures. As a male who does a significant amount of housework I thought it was sexist.

The next panel had Derek Motion from Western Riverina Arts (where I also work) guiding a conversation with graphic novelist Pat Grant and travel writer Jorge Sotirios on 'a clash of cultures'. Grant thought it was a refreshing topic as he'd previously been put on panels talking about surfing, where he'd gotten a 'dressing down' for describing the culture as being full of jocks and sexists. He said he also got stuck talking on racism, as his book Blue developed from experiencing the so-called race riots in Cronulla late 2005.

Sotirios had also been in the area on 11 December, when much of the action had taken place. He cited a friend from the area who'd thought the riot had been "the icing on the cake of a drug turf war".

Grant recalled he'd ended up at the beach for a swim after selling zines in Wollongong earlier in the day. "What we'd seen was mundane and sorta boring," he said. "I still can't reconcile my experience with what everyone else seems to know".

People had been getting drunk but there was a militant racist element who'd been driven to the area because it had been promoted as a day of action by right-wing commentators. Sotirios thought "a lot of surfers don't want to beat people up. That event was manufactured by people on radio like Alan Jones. It led to an escalation of problems and just went from bad to worse".

Grant observed that surfing culture has changed and I think other commentators have observed Australia has moved further to the right in recent decades. "Your average surf mobile used to be a Kombi with seven longboards on top. Now it's a ute with a racist sticker on the back."

"I tried to work out my feelings in an elaborate book," he said of Blue. "You're looking for answers but there aren't many in my book."

Sotirios replied there's "danger in getting caught up in the imagery of an event," leading Derek to comment on the subterranean creatures in Blue.

"I avoided pointing the finger and used what I knew about the language of comics to create a short-cut to that feeling of otherness," agreed Grant. This was good for avoiding making a reader feel bludgeoned by metaphor. He compared it to a Kafka story about a man waking up as a cockroach, "a visual metaphor for a cultural other".

"Comics have a tradition of creating this sort of visual juxtaposition," said Pat Grant, mentioning Spiegelman's Maus and the representation of Polish people as pigs as one provocative example.

Sotirios spoke on using life material in his writing, saying it requires careful selection of the experience. "You have to laugh at yourself," he said. It's dangerous "to point at other cultures. You've got to be careful using your own life history because you've got to be able to bring it to the reader".

Grant expressed regret at his superb work Toormina Video, which led to Jorge expressing surprise that he regretted it being good and popular but it is a very personal account of his father's alcoholism. "It's awesome because a lot of the love come back," he observed. "It's awesome that people are now on the same page but I'm not looking forward to talking to my aunt about it."

Sotirios reflected that one friend he'd portrayed had been unhappy with being shown as a clown but didn't criticise another writer for revealing his drug use. "You just have to wear it," he concluded.

"Storytelling is a tricky business," agreed Grant. He mentioned a friend who'd written a family member out of a story. "The reading public think he's baring his soul but I know he's crafting it and it's manipulative."

Deb Stevens returned to the stage to host a conversation with Freda Nicholls and Deborah O'Brien on their historical writing, fiction and non-fiction. O'Brien spoke of the contrast in social changes in her work The Jade Widow and that she'd had feedback from younger readers that they related to the setting of the 1920s and '30s.

Freda Nicholls explained that she'd written for R.M. Williams' magazine and the opportunity to write a book had arisen after an Australian Story profile on her sister had led to inundation from viewers, "who took heart from many parts of her story and wanted to talk about it".

The book Love, Sweat & Tears deals with suicide, which had some resistance until the publisher had pitched that it might help someone. Nicholls' sister had made the book conditional on her writing it and the first-person perspective had proven a challenge which was further extenuated by their five-year age difference. She'd been surprised by the opportunities the process presented to get to know each other and said "going into my own past was a very cathartic experience".

Nicholls admitted the book glosses over some details to avoid hurting people and legal staff at the publisher directed changes to avoid libel. One example was the advice given by a doctor who was proven wrong in declaring her sister would never walk again. "If people are still alive you have to be careful," she said before describing her current work on the 1950s shearers strike as 'liberating'.

O'Brien had a different perspective on going into the past through her research for novels. She spoke of experience learnt through cutting historical information. "When readers ask 'do you do much research?' I think uh-oh" because it distracts from the storytelling. Her editor advises on information to remove, a pain that is softened by pasting this material into a folder rather than just deleting it.

Host Deb Stevens raised the topic of how Google is changing audiences as it becomes easier for them to quickly research historical facts. O'Brien replied "The Downtown Abbey syndrome is the new reality" and went on to recount how hearing the phrase 'steep learning curve' on the show jolted her, as it's an expression with origins in the 1980s.

Susan Toscan spoke from the audience to quote Bryce Courtney: "Don't write what people already know". An observation that a better informed readership means an author can avoid covering some historical detail.

O'Brien is a fan of primary sources for her research, including newspapers. "I have a moral obligation to depict historical characters realistically."

Nicholls said she loves using Trove but doesn't trust newspapers, having worked on them. O'Brien then made a comment that picked up on Grant and Sotirios' earlier panel: "Sometimes it's harder writing about recent history because people have a memory of it".

Another comment from O'Brien concerned the process of writing. She spoke of having internalised the structures and frameworks of novel and this allowed her to write about "free-range characters," free from following a rigid outline for a book.

Alison Green from Pantera Press took to the stage with authors Wanda Wiltshire and Rebecca James to discuss their supernatural fiction. The opening question focused on their inspirations and Wiltshire had a fascinating start to writing. She described not knowing what to do with her life and quoted a line from a favourite song on how the some of the most interesting people don't know what they want to do with their life. "That's me, except for the interesting bit," Wiltshire said.

She recalled that after "finding god" she asked what she should be doing with her life and the words 'write a book' came to mind. Wiltshire went to bed seeking inspiration and awoke with the story that will unfold over six or seven novels, beginning with Betrothed.

James had a different introduction to writing. After foregoing studies in Arts/Law to support her family, she needed something to do and began "dabbling". Her sister is also an author and encouraged her to persevere with the process and sending manuscripts to publishers. The day after James and her husband closed their business, a publisher bought her book.

The idea for James' novel Sweet Damage came from experience with agoraphobia. She undertook some research and magnified her own knowledge, as well as reading online forums and texts but "I wasn't presenting a medical view of it".

Wiltshire said there were "definitely elements of me and other people" in her work. She drew on her son, people she went to school with and created a leading man who "is every girl's fantasy -- mine anyway".

James quoted author Anne Fine: "It's not that you write about people you know. You write about what you know about people." She thought relationships are the most interesting thing about all stories.

The day concluded with all the authors being asked what book they wish they had written. (Pic above courtesy Western Riverina Arts.) A variety of titles were suggested but, maybe because it was the end of the day, the discussion seemed a bit flat. Rebecca James was of the view there were none: "I have no books but there are things I wish I could write better".

Wanda Wiltshire said "they're of other people" and this was some comfort for Jorge Sotirios, who said "I'm glad others have written books for the torture they've gone through".

The Griffith Readers Festival was a fascinating day for the stories presented and a sense of the challenges faced in writing them. I was disappointed not to engage Pat Grant in discussion because I read a lot of graphic novels and, living in a small town, don't get much opportunity to talk about them. It was great they had a graphic novelist as part of the day though, hope this continues next year.